Social reality is founded in what a community agrees to be real. Whereas physical reality exists independent of a human observer, social reality is built through human language in the form of ideas and categorisation. A country is a social reality. Money is a social reality. The legal system is a social reality. A democratic system is a social reality. Your job is a social reality. These things exist because we and others agree they exist. When we stop agreeing, they cease to exist. The human world is literally built through social reality.

We can all generate an aspect of social reality. Make something up, name it, and you’ve created a concept. Share this concept with others, and if they agree, you’ve created something socially real. We do this by imposing new functions on aspects of physical reality that go beyond their physical properties and sharing those concepts with others.

In this work, we categorise our internal experiences as emotions using emotional distinctions to make these sensations meaningful. Rather than an emotion being a thing and part of physical reality, we construct instances of happiness, sadness, guilt and so on. Emotion concepts are part of our social reality because a community agrees on them. We move our facial muscles all the time. We frequently furrow our brows, wrinkle our nose, widen our eyes, close our mouth tight shut and so on. These actions aid us in observing the world. For instance, widening our eyes improves our peripheral vision to expand our field of view, so we can see more. These movements are not intrinsically emotional. The same came be said for our internal motion as we regulate our body throughout the day.

Yet sometimes, we interpret the furrowing of our brows, the wrinkling of our nose etc as an emotion. Other times we do not. Movements and bodily changes become instances of emotion only when we categorise them that way. Without emotion concepts, there are only moving faces, beating hearts, circulating hormones and so on.

That is not to say emotions are not real. Fear and sadness are real to people who agree that certain changes in the body, on the face, and so on, are meaningful as emotions. These interpretations are powerful as they are shorthand for how I am interpreting a situation. I only need to smile at something you say for you to interpret how I feel about it. I could say “that is very amusing” but a smile will far more simply convey that meaning.

It is important to point out our interpretations are just that. When we create an interpretation of an instance of emotion in someone else, we are guessing. If we think someone is angry and check with them them then they may agree or disagree. However, even if they agree, they may have a different interpretation of anger and what it means. I may think anger is simply blowing off steam, but you may see it as a totally inappropriate emotion that is a prelude to violence. These differing distinctions mean we may have a common concept we call anger but still create different meaning about that concept.

The more emotional concepts we have and share, the more we are able to interpret our and others’ experiences. This means our predictions become more effective and we can better navigate life.

However, much as it may be surprising to many, no emotional concepts are universal. To quote Lisa Feldmann Barrett in her book, ‘How Emotions are Made’,

“Utka Eskimos have no concept of “Anger.” The Tahitians have no concept of “Sadness.” This last item is very difficult for Westerners to accept . . . life without sadness? Really? When Tahitians are in a situation that a Westerner would describe as sad, they feel ill, troubled, fatigued, or unenthusiastic, all of which are covered by their broader term pe’ape’a…

Beyond individual emotion concepts, different cultures don’t even agree on what “emotion” is. Westerners think of emotion as an experience inside an individual, in the body. Many other cultures, however, characterize emotions as interpersonal events that require two or more people. This includes the Ifaluk of Micronesia, the Balinese, the Fula, the Ilongot of the Philippines, the Kaluli of Papua New Guinea, the Minangkabau of Indonesia, the Pintupi Aborigines of Australia, and the Samoans. More intriguingly, some cultures don’t even have a unified concept of “Emotion” for the experiences that Westerners lump together as emotional. The Tahitians, the Gidjingali Aborigines of Australia, the Fante and Dagbani of Ghana, the Chewong of Malaysia, and our friends the Himba from chapter 3 are a few well-studied examples.”

Suffice to say, the emotional reality varies between different societies. Sometimes in subtle ways but sometimes in significant ways.

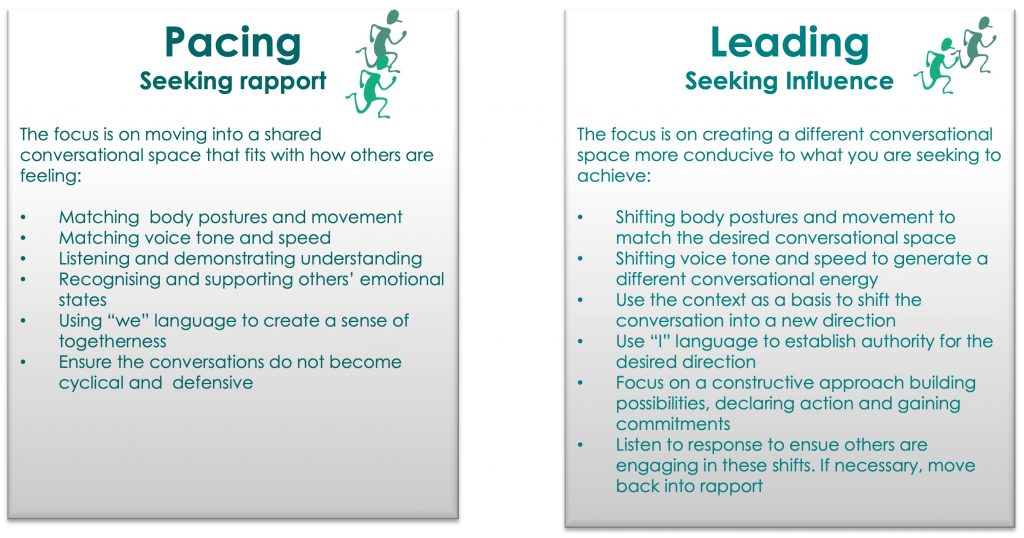

Pacing and Leading

For a long time we have known two interacting people will move into a physical synchronicity with each other. We will tend to match posture, heart rate and also create a common emotional space. We also impact each other’s body budgets leading to and impact on each other’s emotions. With this in mind, we can conclude our emotions are contagious. The implication is unconsciously two people will fall into a common emotional space and the interpretations and predispositions accompanying that space. Understanding this contagion provides those who have more emotional mastery with the opportunity to bring others into their emotional space. Being attuned to the emotional dynamics, provides the chance to synchronise being with the other to build rapport or shift postures and language to lead into a new emotional space. This is one of the key aspects of influencing others and is known as ‘pacing and leading’.