Through our conversations, we also build up stories about our shared experiences. These stories form the basis of commonly held meaning and future interactions. In communities, over time these stories develop into bigger narratives into which come other people. For instance, families develop ‘meta-narratives’ about the family and its norms and traditions. We born into those narratives and adopts variations of them as their own. As we grow, we become part of other communities such as schools, sporting clubs and work organisations, and those communities have narratives about norms, traditions and so on. On life’s journey, we have to find ways of integrating those meta-narratives to feel part of those communities.

The impact of those narratives on us is profound yet largely transparent to us.

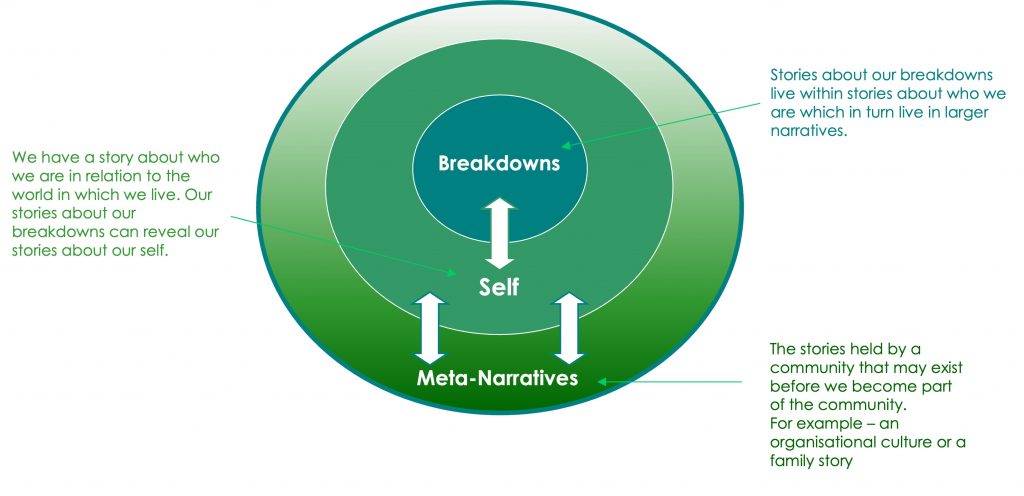

Examining our self-stories and our explanation of our breakdowns can uncover links between those stories and the meta-narratives in which we have lived and those in which we continue to live. They can be seen as a set of three Russian Dolls with the meta-narratives sitting outside our self-stories which in turn sit outside our stories about our breakdowns. This is defined as ‘three levels of story’.

As we are all unique observers, a breakdown is a breakdown for us because of how we observe the world. When someone speaks about their breakdown, we can listen beyond the breakdown and make interpretations about their self-story and the meta-narratives in which they live(d). We also assume people who live in certain meta-narratives are likely to have commonalities in their self-stories and their breakdowns.

Meta-narratives hold communities together. By sharing a common story, we gain common distinctions and the comfort of other people who seem to share our worldview. When we seek to build a relationship with someone we tend to initially seek and focus on what we share in terms our concerns.