Before telephones became common place, people used to communicate over long distances by telegraph via a sequence of electrical impulses. ‘Morse Code’, which involves patterns of short and long taps, identified as dots and dashes, was developed as a means of communicating in this way. These patterns of dots and dashes represented letters. For example, ‘dot dot dot’ represented the letter ‘S’ and ‘dash dash dash’ was an ‘O’. The universal call for help ‘SOS’ then is ‘…—…’.

To the untrained observer, Morse Code would just be incoherent noise, but for someone who understands the code, it translates into letters and words. Although it might not seem like it, this is also the case when it comes to anything we hear. Sound waves enter our bodies and we make them into something that has meaning to us. We can distinguish words and sentences and we know what those words and sentences mean to us. Other sounds, we might distinguish as music or someone clapping their hands. How we distinguish things from each other is defined as making ‘distinctions’, the patterns relating to those distinctions as ‘connected distinctions’ and the meaning from those distinctions and their connections in certain contexts as ‘stories’.

Our distinctions are mental concepts that allow us to identify phenomena, separating one thing from another. Distinctions relate to the boundaries we place around aspects of the world. I can look at the table in front of me and distinguish a cup from the tabletop. I can see where the tabletop ends defining where the tabletop exists and where it does not exist for me. I can define what is me and what is not me.

Distinctions are not universal and pre-ordained; they are created by individuals and communities.

We initially derive our distinctions from patterns we observe. When we are born our senses are bombarded with signals externally from the world and internally from within our body. However, there is structure and regularity in those signals. Researchers have identified an ability for babies to learn patterns, a process termed ‘statistical learning’. Statistical learning is a process of identifying what goes with what more often than not. Edges form a boundary. Those two things are part of a bigger thing. Very quickly infants bring vague sensations into patterns. We see faces and hear words and the world starts to make sense to us. Statistical learning is not the only way we learn but it plays a very important role in shaping how we experience ourselves and the world early in life.

Distinctions held within a community are created in language and shared with individuals within that community through observation and language. We learn them from others. Those distinctions allow that community to intervene in certain domains of action in certain ways. Examples of this can be found in any profession and the distinctions of relevant professions allow members to build bridges, fix teeth, practice law and so on. It allows people in a community to observe the world in a certain way. We perceive the world through our distinctions.

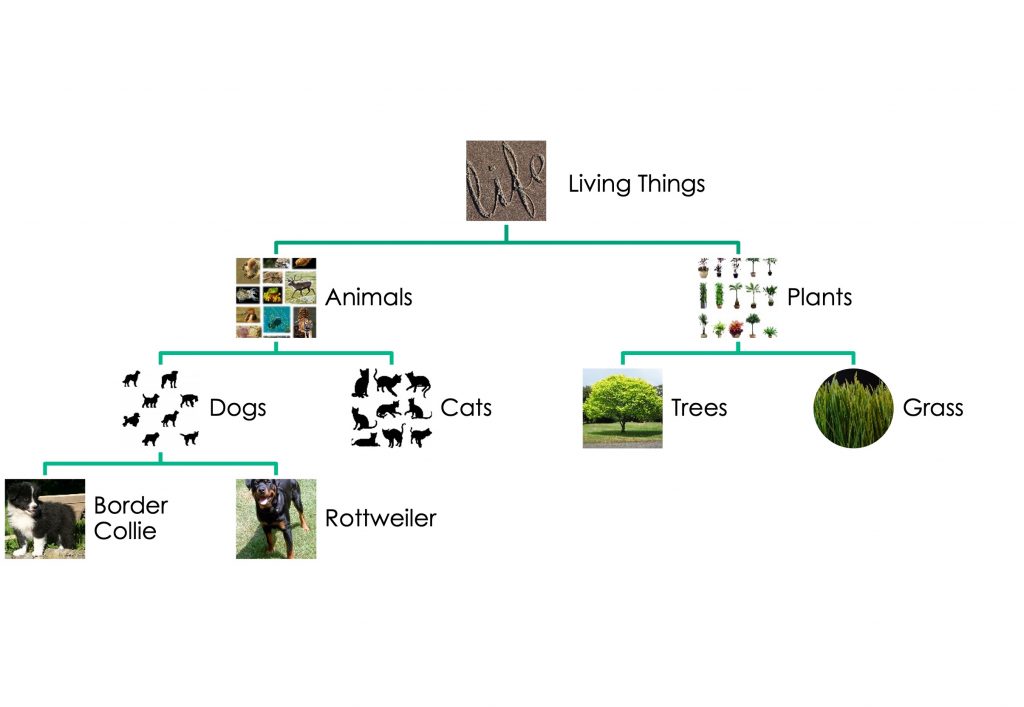

Distinctions not only relate to specific things but can be combined into ‘connected distinctions’ that relate to patterns or groups. This is the basis of categories. Take this example:

- A ‘border collie’ is a ‘dog’

- A ‘dog’ is an ‘animal’

- An ‘animal’ is a ‘living thing’

Each of these distinctions allows us to speak to connections between things, in this case an aspect of a hierarchy of life. Once again, these connections are defined by the community in which the distinctions are held.

Connected distinctions are not just ways of categorising objects but are also be related to our concerns. For example, we can have a distinction of ‘things we could use to give us light’. Such a set of connected distinctions could include the sun, a flashlight, a lit match and a mobile phone. Each of these things has little in common with each other except that they can provide us with varying degrees of light.

It is important to appreciate our distinctions are not purely a linguistic phenomenon. All living systems have distinctions in some way. For example, animals, if they are to survive, must learn to distinguish food from things that are not food. However, language provides an incredible advantage to human beings. We can use language to share and connect distinctions, create complex conceptual distinctions, and thereby design our societies and ways of being, and develop and build technologies.

From our distinctions and our past experiences in relation to those distinctions, we then develop stories whereby our experiences mean something to us. Our past experiences include our own personal interaction and the interactions we have had with others’ stories about those distinctions. Our stories reflect our concerns in life. Our distinctions and stories underpin our simulations and guide us through every situation we encounter.

Say I encounter a dog I distinguish as a Rottweiler, then the stories I have of Rottweilers from my past will generate predictions about this encounter. If my past experiences are mainly of Rottweilers as aggressive dogs, I will be predisposed to simulate a way of being to deal with aggression. This means our stories are contextual. The distinction of a Rottweiler as a dog is connected to other distinctions about what such a dog can do. Based on our experiences of dogs, we have assigned meaning to that network of distinctions to create our story of what a dog means to us. We take those stories into a situation where we encounter a dog and form our story of what that dog means to us in the moment.