Human beings live in a complex web of linguistic commitments with each other. We create these webs through the practice of ‘coordination of future action’. This distinction speaks to more than just coordinating action, which can take place in the moment and apparently without language. All social animals coordinate action in some way – that is what makes them social. However, through our sophisticated use of language we are able to coordinate complex action in the future.

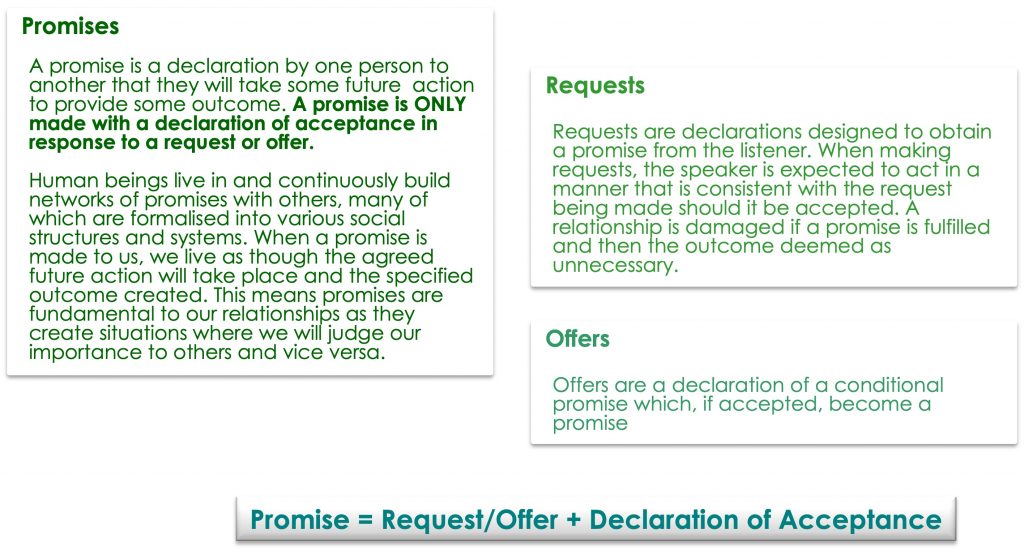

There are three types of declaration specific to the coordination of action between human beings – promises, requests and offers.

Promises

A promise is a declaration by one person to another they will take some future action by a specific time. Human society is built on promises. The world in which we live is full of promises we make and that are made to us. They are an indispensable part of being human.

Through promises, we enlist the help of others to expand our capability in life and take care of much broader concerns than would otherwise be possible by acting alone. Our social structures and personal relationships can be seen as networks of promises. Indeed, one way in which we can assess the scope of our authority is the extent of the promises we can obtain from others. Those with greater authority can gain more significant promises in the world.

When a sincere promise is made, there is a change in the individual realities of the two people involved and they act as though whatever has been promised will occur. If I promise to go to the movies on Thursday evening, it is assumed that we will both head to the movies come Thursday. Unless you think I will not fulfil my promise, you will expect me to show up. You may well make promises to other people or handle requests from others based on my promise to you. So, it is we continually build networks of promises.

However, there is more involved in promises than just the linguistic act of making a promise. Once it is made, some action must also take place for the promise to be complete. Unfortunately, despite our best intentions, we do not keep all our promises. When breaking a promise, most people only consider the immediate implications and what they have to do to placate the other person and move on with life. However, we are constantly making assessments about what happens and the actions of the people around us. We use those judgments to navigate the future. Every time a promise is broken, we make assess the trustworthiness of other person and the dynamics of relationship with them can be altered.

The coordination of action and making a promise must always involve two people. The person making the promise and the person to whom the promise is made. As such an effective promise must always involve at least the following:

- A speaker

- A listener

- Some future action, and

- A timeframe

As there are always two people, making a promise involves not one but two linguistic acts. The linguistic act of declaring a promise is always preceded by the linguistic act of either declaring a request or declaring an offer. It is the declaration of acceptance of the request or offer that creates the promise. A promise is created with a declaration of acceptance in response to a request or an offer.

Requests

Requests are declarations designed to obtain a promise from the listener.

We make a request when we have identified something is missing for us and we believes someone else can provide what we need. We then declare a request seeking a promise from them to provide what is missing . In making a request and getting the desired promise from someone, we become responsible to act in line with our request. To do otherwise is to potentially damage the relationship between us.

Offers

Offers are declarations of a conditional promise.

When making an offer, we are proposing a promise that comes into being should it be accepted by the other person. The responsibility of the promise lies with us should the offer be accepted and, we would be expected to act in accordance with our offer.