We are always stepping into an unknown future and assessments are the linguistic aspect of weighing risk and navigating that uncertainty. Our assessments are automatic and born of our way of being in that moment. They also reflect our experience and what has worked to take care of our concerns in the past. Our habitual assessments will generally work well for us yet sometimes they do not and we find ourselves in significant breakdown. When this occurs, one way to learn from the experience is fo through a process of grounding our assessment.

The goal is to find a new way of assessing how to navigate situations and potentially to have conversations with others to affect change.

Before beginning this process, be clear about the assessment itself. It is easy to make broad generalisations about our experience however to take action generally requires a narrower focus.

The process to ground an assessment involves five steps:

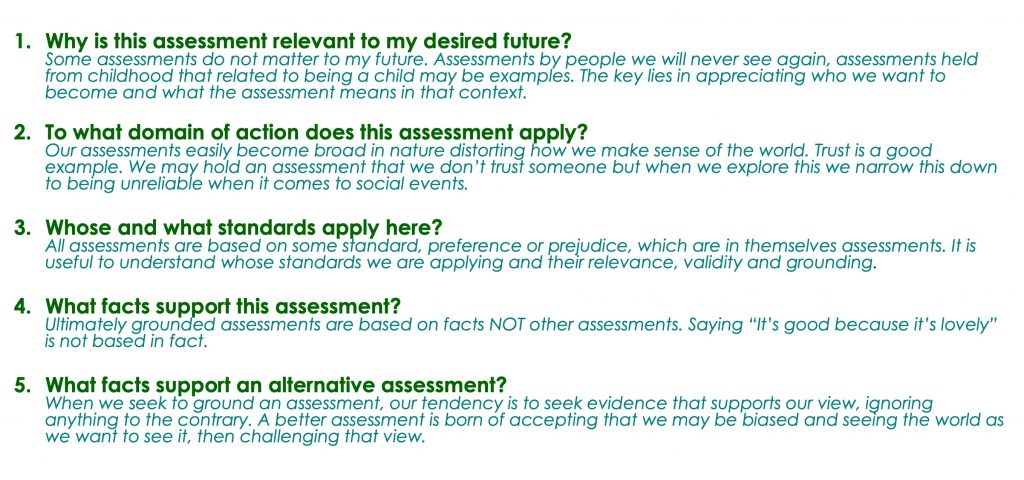

1. Why is this assessment relevant to my desired future?

Our assessments orient in the present to the future, yet the present is always becoming the past. An assessment made yesterday still reflects and shapes our world-view. However, is it still relevant to us today?

In answering this question, we often find many long-held assessments shaped at a certain point may have been useful then but are no longer appropriate for us at this stage of life. We may also discover something about our ways of being and worldview that is inconsistent with who we want to become. Such breakdowns can open up opportunities to learn and grow and find better ways of orienting ourselves to the future.

2. To what domain of action does this assessment apply?

We make assessments related to our observations in a certain domain of action. It common to extrapolate our assessments beyond that domain and their experience. A common example is generalised assessments of trust that show up in comments such as “I do not trust him.” This is all-encompassing statement about someone that leads to little or no means of building a healthier relationship with that person. It would be more useful to identify what they do to generate that assessment. It could be you believe they are not honest about some situations at work or they keep breaking promises they make to you in social settings.

Clearly identifying the domain of action establishes a stronger basis for an assessment and a way forward should we want to take more effective action to address a concern.

3. Whose and what standard am I applying here?

Assessments speak to our worldview and what we see as good and bad for us in the world. These determinations move us towards things we think are good and away from the bad. Over the years, we have developed some general assessments about the world that form our preferences and prejudices in life. These speak to our standards in life.

When grounding an assessment, we can challenge those standards and their source. This may point to more deeply rooted assessments that may cause recurrent breakdowns.

4. What facts support this assessment?

A grounded assessment is supported by factual evidence. That means true assertions.

An assessment cannot be grounded by other assessments. To say “I think Jill is horrible because she is a not a nice person” is simply putting two assessments together in an attempt to make our assessment sound grounded.

When grounding an assessment, we can weigh the facts as they relate to the domain of action and the standards we are applying to test the assessment’s soundness.

5. What facts support an alternative assessment?

Confirmation bias is a well known psychological predisposition whereby we look for evidence to support our view and ignore evidence to the contrary. Although this may help us feel more certain about life, it can also blind us to what is really happening.

With that in mind, we can look for facts that disprove our assessment and then compare both sets of facts before validating or changing our assessment.

Grounding an assessment is not just a process to justify our view, it is also a means of identifying opportunities to change our worldview creating a more useful context for future action. This can also provide ideas about missing conversations to address our breakdowns. For example, we might identify a need to create some shared standards with colleagues so that we can work more effectively together.

The process of grounding assessments is useful in many situations such as giving feedback to others and learning from significant breakdowns where things have not gone well for us