We all experience affect, our sense of pleasantness and arousal. However, affect stems from interoception involving all internal sensations, so when is that sensation an emotion and when is it not? Indeed when we believe it is an emotion, how do we know which emotion?

It has long been theorised that all human beings experience the same emotions and it was assumed research would find clear internal identifying biological characteristics when these emotions occurred. Recent neuroscientific research has found these assumptions to be false. Even a cursory investigation of an emotion such as anger can help us understand why. When we think of anger, we tend to think of someone yelling, banging the table and going red in the face. This is the stereotype but we also know that people can sit and seethe in anger, speaking quietly but coldly. Or they can smile, whilst seething on the inside. Indeed, there are many forms of anger as there are with all emotions; variation is the norm. Each of these forms of anger also entail different physical experiences. Rather than a specific biological pattern there are many different instances of affect that we interpret as the same emotion.

The key here is the idea we interpret our inner experience as we do all of our other sensory experiences. Our interpretations are born of our core concerns, our distinctions and the context in which we have the experience. Those interpretations then provide a context for further interpretations and so on. Consider this example, you are about to meet someone you have admired for a long time and you experience a flushing sensation in the face and butterflies in the stomach. If you are expecting the meeting to go well, then you may interpret this as excitement. If you are concerned the meeting will not go well then this could be interpreted as anxiety. The sensations are the same but our emotional experience is difference due to our expectations and predictions.

This variety leads to the conclusion that our emotional experience involves interpretations of instances of emotion based on affect, context, distinctions and concerns rather than a recognition of an emotion as a specific biological function. It is also useful to appreciate that this interpretation is automatic and happens outside our awareness. We do not choose a specific instance of emotion, over time we have developed distinctions of how we should act and our emotions are pointing to those predispositions.

We have learnt our emotional distinctions from others who have connected certain emotional words with certain experiences. The implication is, rather than emotions being consistent for all humans, they are constructed as a social reality within communities. This is shown in research that identifies different cultures having different emotional distinctions and experiences. However, the incursion of western culture throughout the world is leading towards broader consistency of what are seen as the standard western emotional distinctions such as categories for anger, sadness and so on.

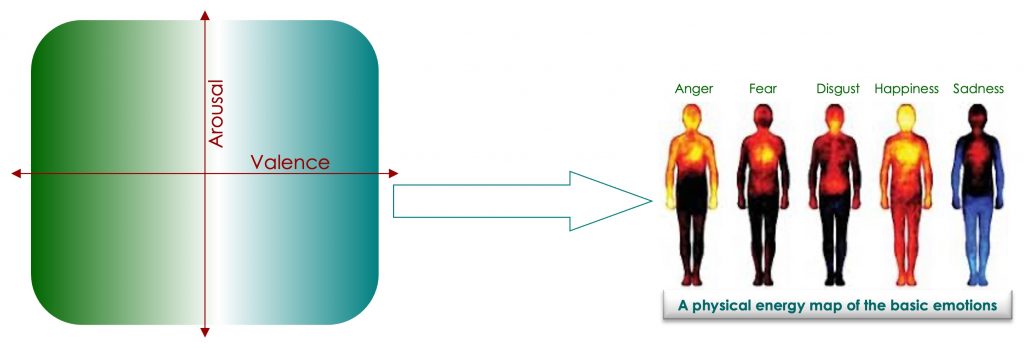

The social construction of our emotional life means we learn to distinguish emotions from others. We are certainly born with a capacity to notice affect, that general sense of feeling, but the nuances of the combination and variations of valence and arousal, and what they mean, are created linguistically. When we categorise an emotional state as anger, we use our distinctions and stories of emotions in the context of the situation to identify an emotional pattern and then distinguish the state as ‘anger. This is the case for all of our emotional states.

So, this is how we construct instances of emotion:

- Our brain creates predictions and simulations about what will happen next;

- Those simulations initiate internal activity to ready us for what is predicted;

- Our interoceptive network manages our body’s resources and provides us with sensations of affect – valence (pleasant and unpleasant) and arousal;

- Based on our distinctions and stories in relation to our concerns at that point in time, we seek to make sense of those internal sensations and create meaning;

- That sense of meaning is fed back into our predictions setting up our simulations and, ultimately, our experience of the world.

Ultimately, the extent to which we can understand and learn from our emotional life lies in the fineness of our distinctions and how well we understand our concerns. This is the basis of ‘emotional intelligence’, which allows us to move past feeling simply good or bad into appreciating and dealing with a rich emotional life.