A common-sense view of our experience would have us believe our brains react to what our senses tell us about the world. We perceive something, process what we perceive and then take some sort of action. That a stimulus leads to some brain activity which leads to our actions would, at first glance, seem to be how we engage with the world. Indeed, it is not uncommon to hear people speak of the idea that stimulus leads to thinking leads to response. But think about this for a minute.

If this is the case, our experience of what is happening would always be some time after what was actually happening. What are the implications if this were true? Simply put, we would struggle to survive. Things would have happened in the world before we could respond to them; and some of those things would harm us.

Clearly the idea that our reactions will always come after an event in the world need to be re-assessed. Recent advances in our understanding of the brain’s role, and particularly the introduction of sophisticated brain scanning techniques, are turning our common-sense view of the brain on its head. It appears that rather than reacting to our sensory perceptions, our brains are constantly predicting what those perceptions might be.

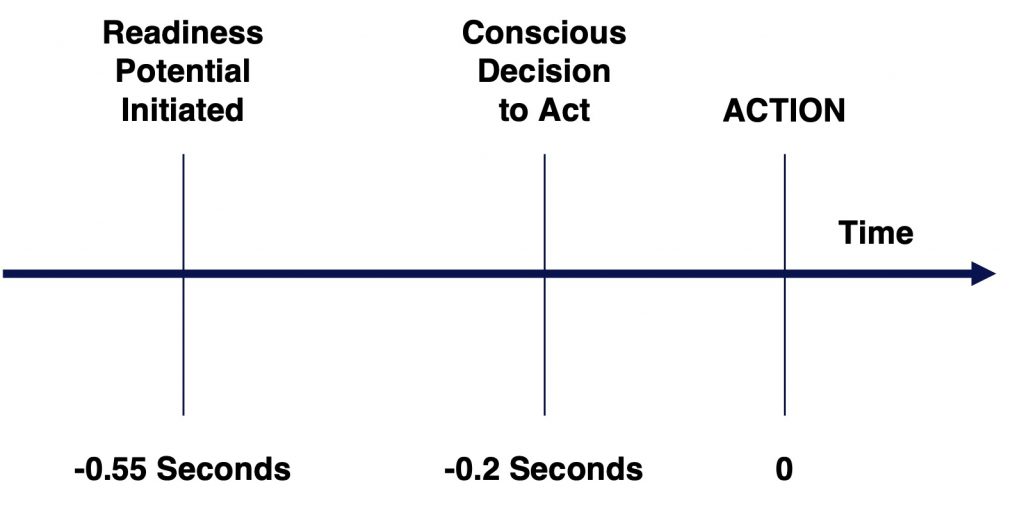

In the 1980s, neuroscientist Benjamin Libet conducted studies to examine what initiates action when a person chooses to flex their wrist. To do so, he measured the timing of three things – the beginning of brain activity in the motor cortex, the conscious decision to act and the start of the movement.

The results, which have been reproduced by others, yet still promote debate today, challenged the established view of the role of the brain, consciousness and even free will. Libet found that the decision to act occurred about 200 milliseconds before the action. However, the readiness potential, which is the start of brain activity associated with the action began about 350 milliseconds before the conscious decision – about 550 milliseconds, over half a second, before the action. In other words, the brain processes required for the movement began over one-third of a second before the person made the conscious decision to move. In the context of brain activity, this is a very long time. It seems we are in the process of acting before we make the conscious decision to act.

A recently uncovered principle of how the human brain works may give us an answer to this anomaly. Rather than lying dormant waiting to be stimulated, the neurons in our brains are constantly firing, stimulating one another at various rates. This ‘intrinsic brain activity’ is one of the great recent discoveries in neuroscience and appears to involve our brains making predictions of what we will encounter next in the world based on our past experience. Our brains do not react to external stimuli; our brains are predicting what those stimuli might be and then assessing the result.

The majority of these predictions are at a micro level, predicting the meaning of bits of light, sound, and other sensory information. Every time we hear speech, our brain breaks up the continuous stream of sound into phonemes, syllables, words, and ideas based on distinctions we have learnt, and predicts what will come next. Other predictions are at a more macro level. You are interacting with a friend and, based on context, your brain predicts that she will smile. This prediction drives your motor neurons to ready your mouth in advance to smile back, and your movement causes your friend’s brain to issue new predictions and actions, back and forth, in a dance of prediction and action. If sensory input indicates any predictions are in error, your brain has the capacity to correct them and issue new ones. All of this happens very rapidly and outside of awareness.

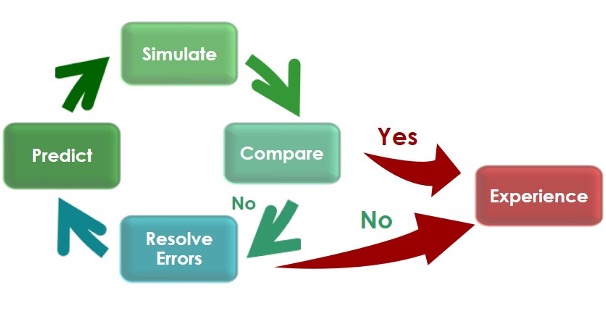

Being plastic, our brains change as we go through life. Experiences create memories and shift neuronal function and connection. Our past experiences become embodied to varying degrees and form the basis on which our brain makes its predictions. These predictions initiate meaningful ‘simulations’ of what might be. These simulations also happen rapidly and outside our awareness and involve all aspects of our experience – our perceptions, our internal physical experiences including our emotions and our thoughts and words. Should a prediction match our sensory perceptions or internal sensations then our simulation becomes our experience. In this approach, we speak of this as being in ‘transparency’.

Intrinsic brain activity is continuous, occurring even when we are asleep. This leads some to propose that our dreams involve the same prediction and simulation process, which, unchecked by sensory input, veer all over the place.

However, not all our predictions match our sensory input. When this occurs, we find ourselves in a ‘prediction error’ and we must rapidly create a new prediction that better matches the new information. In this approach, we speak of this as being in ‘breakdown’.

Your simulations will generate certain internal action and a shift in body resources creating internal sensations we distinguish as emotions and those feelings will drive a feedback loop providing a further context for your predictions and simulations and ultimately how you think, speak and act.

Very quickly, you will engage based on your best guess of how to act. Sometimes the prediction error is resolved, other times we ignore the error and go with our initial prediction. Either way, what follows will be your experience and may predispose you for future similar breakdowns. Ultimately, your simulation does not have to match objective reality for it to become your reality.