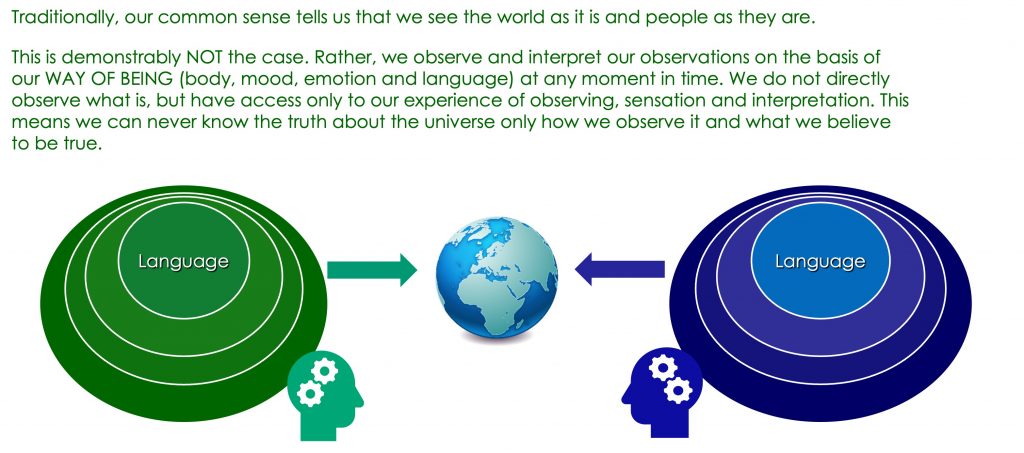

It is easy and somewhat intuitive to believe when we observe the objective reality, we actually observe it as it is. Yet, this is not the case. We experience and engage with the universe through our way of being and that experience is all we know.

As our way of being in any given moment is a product of our own unique journey through life, it follows the way in which we observe and experience the universe is unique. We are indeed unique beings in an ocean of unique beings.

So, what does this all mean?

It may seem like a trivial distinction to make but the implications of seeing each of us as a unique being is profound. For instance, if I do not make that distinction and also believe I see the world as it is, then I must also assume everyone sees the same world. These assumptions create a problem for me if you voice a different view to mine. If I see the world as it is, and you disagree then one of us must be wrong. If I usually see myself as right, it is an easy step to become an arrogant holder of the ‘Truth’ and to see you as somewhat stupid. After all, how could you not see what is right in front of you! If I usually see myself as wrong, then I it is a short step to see myself as flawed. Neither approach will lead to a a fulfilling sense of sense or healthy ways of relating to others.

On the other hand, seeing myself as a unique interpreter of the world amongst other unique beings, I can start to ask myself why others see the world differently to me. This approach opens up the possibility of having access to other interpretations of reality and an appreciation of other people as different observers. Rather than seeking to convince others of the rightness of my worldview, I can seek ways to find common interpretations. This approach removes the need to make others wrong, something very few people like to feel, and means we can find better explanations of the phenomena observed by many.

Let’s look at a very topical example to explore the difference – the human impact on climate warming. There are two aspects of this – the data and what it means. Firstly, the data. There is an enormous amount of data related to the Earth’s climate. No one person is likely to have access to it all, let alone be aware of the existence of all of it. A vast amount of that information is captured and shared but certainly not with everyone. So, it is important to appreciate everyone has varying degrees of partial knowledge of the total dataset. Even our computer systems, which can access much of the data, are certain to be deficient to some degree. Like two people in back and front of another person, we observe different things – one sees the back of the person’s head and the other their face.

Ultimately this means that everyone observes from a unique perspective even if we are in the same circumstance. So, going back to climate change, everyone starts with a unique set of observations based on what they have encountered and noticed. As I will discuss elsewhere, we first see what we expect to see. This often means we will not observe or ignore phenomena that does not fit with our expectations.

The overwhelming majority of us know little of the data, but that will not stop us having an opinion about climate change. Our opinions are formed in the context in which we make our observations. That context involves our pre-existing interpretations including our core concerns, biases, standards and so on.

If our main concern in life involves living day to day, then a more distant concern such as climate change will mean little to us. For others concerned about nature or the future of their children, it will be more important.

To simply argue the data tells us all we need to know to take dramatic action, ignores the distinction that we all interpret the world uniquely. If we are to develop shared interpretation of any circumstance, then it is important to focus not just on the data but on the way in which it is interpreted and the shared context within which those interpretations are made.

By recognising the human view of the world is one of interpretation, we can put ourselves in the space of being able to judge whether other interpretations might serve us better than the ones we hold. Ultimately, coming to agreement about our interpretations is the substance of more effective conversations and relationships.