Our way of being is not static but shifts dynamically through time.

Think about how you feel on any given day. No doubt there will be periods when your energy levels vary; sometimes higher, sometimes lower. Those shifts in your energy level denote a shift in your physical being at that time. There is a different way of being as a direct result of your energy level leading to different predispositions. Sure, many predispositions will be the same but some will vary. For example, many people find themselves in a mood of irritability when their energy is low, whereas they are not so predisposed to irritability when they have a higher energy level.

Another constantly shifting aspect of our physical being is our posture. We sit, stand or lie down. We sit with one leg over the other or feet apart or cross-legged. We can take so many different postures and they each have an impact on our way of being at that moment in time.

As our way of being is dynamic through time, so are our predispositions.

Human being’s have a propensity for seeing patterns. Based on the patterns we see in our ways of being, we generate stories about ourselves which in turn establish what we see as possible and what we are likely to do. We also generate stories about others and use them to predict how they might behave and how we might relate to them.

It is our observations of our patterns of being that underpin our self-story and our identity to others and theirs to us.

However, our observations and stories are not a direct and complete representation of objective reality; it is how we experience reality. To paraphrase the Talmud, we do not see reality as it is, but as we are. Unfortunately, most people do make this distinction. They do not notice a difference between what they observe, their interpretations and reality. They believe what they see is reality. The impact of affective realism also means they add a qualitative aspect to their observations. They see good and evil as things in the world rather than our assessments of the world.

This is one way we trap ourselves with language. Our experience of the world is such that it easy to believe our interpretation of a situation is what actually happened. In other words, we easily overlook the distinction between our observations and the interpretation we put on those observations. We can fail to separate our interpretation (the story) from our observations (the phenomena).

This is a critical distinction. By combining our story with the observed phenomena, we can easily lose the order in which we develop our interpretations. We may not see that our interpretations colour our observations which in turn colour those interpretations.

At this point, let’s re-introduce the basic linguistic acts of assertions and assessments as a way of developing this distinction. You will recall assertions are our descriptions of what we observe. For example, “The door was open. I walked in. I shut the door.” Assertions – the words follow the world – are ultimately true or false. They relate to something that already exists for us. Assessments on the other hand provide our bridge between the past and the future. We make assessments about what we observe with a view to the future. As assessment is not true or false but valid or invalid based on the authority given to the speaker; grounded or not grounded based on the facts supporting the assessment.

We do not generate meaning through our assertions alone; meaning largely comes through our assessments. Our assertions describe what we observe – the phenomena. In making assessments, we generate stories of what things mean for us and how they could be.

Even though assertions and assessments are mixed together in our stories, it is important to recognise that our expectations and observations come first. Here we go back to our predictive brain. We create a story about what we expect to observe and then potentially modify in response to what we have believed we have observed. Our way of being in the moment establishes our way of observing, which occurs within our existing stories creating a complex web of interpretation and understanding.

Being able to distinguish the phenomena from one’s story about the phenomena is a vital part of living a fulfilling and impactful life. Our assessments and, therefore our story, are developed from our way of being – how we see the world. When we listen to a someone’s story, we can listen beyond their description of the world to interpretations of their way of being.

Ultimately our stories of how we are and how the universe is will provide the context for our actions. Yet, we often do not see that we are the authors of those stories. As we create our stories of ourselves and everything else, we can reinvent them. Therein lies one of our great opportunities to create a sense of meaning that may better serve us and our experience of life.

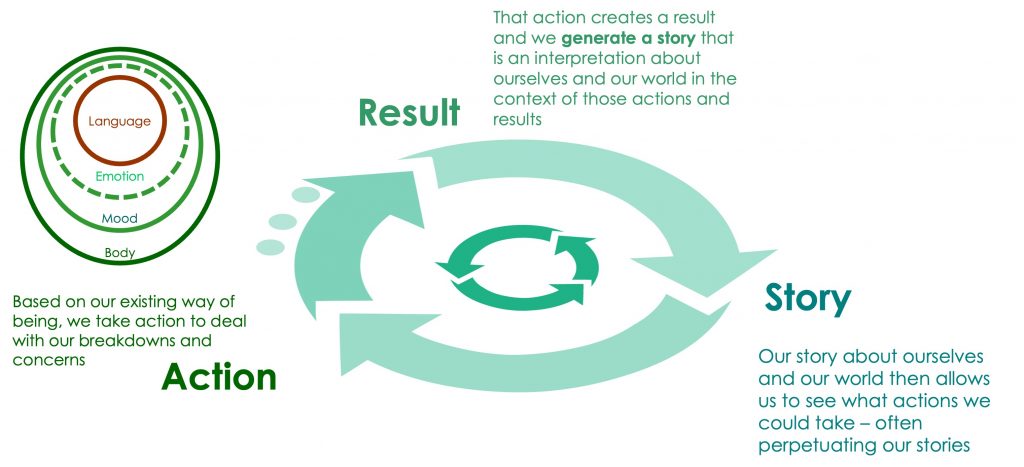

This brings us to the story-action cycle. We act in ways that emanate from our way of being in the moment, reflecting the stories we hold about the world. We interpret the outcome of those actions in terms of our worldview. We also interpret the outcome in terms of our self-story and either reinforce that story or call it into question as we find ourselves in breakdown.

This is a continual process throughout our lives leading to the idea that personal change involves both the development of the stories about ourself and the world and the creation of new patterns of action. These two will always go hand in hand when sustainable change is embodied.