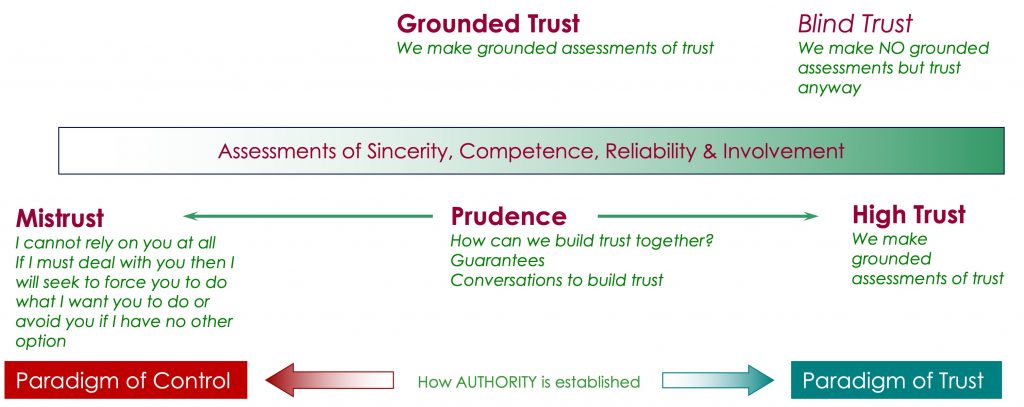

It is all too easy to think of trust as binary – I either trust you or I do not. However, such an interpretation leaves little room to build better relationships. Furthermore, if we interpret trust as the four assessments of sincerity, competence, reliability and involvement then we can never completely trust anyone anyway. As competence is domain specific and, as no-one is completely competent at everything, there will always be areas where someone is incompetent and less trustworthy. If we seek to build better relationships, assessments of trust are more usefully seen as being on a spectrum.

At one end of the spectrum lies ‘mistrust’. Mistrust involves a very negative view of someone. It is generally stems from very traumatic circumstances and suggests no hope of rebuilding the relationship. In mistrust, the clear preference is to end the relationship and never deal with them again. This presents a significant dilemma if we feel we must stay in that relationship such as can be found in the workplace. Mistrust in an ongoing relationship leads to the paradigm of control if we require them to take action for us or passive responses such as avoidance and compliance if we are in a position of lesser authority.

At the other end of the spectrum there is ‘high trust’. High levels of trust in someone can manifest through one of two ways – ‘blind trust’ and ‘grounded trust’.

Blind trust, or naivety, is trusting someone without any consideration of whether or not there is any reason to trust them. It can often be found where there is a large imbalance of power where we see someone as very powerful or even all-powerful, not question their motives and follow them blindly. Blind trust can also show up in close or intimate relationships, where we are overwhelmed by our feelings, hence the saying “love is blind”.

Blind trust can also stem from a lack of a process to ground our assessments of trust. We simply go from our intuition and our sense of them. This is what most people do. We get a feel for people and trust that feel. However, this approach leaves us far more open to our biases heightening the risk in the relationship.

If we wish to be more considered in our assessments of trust, we can utilise the idea of grounding assessments found in the notes on ‘The Domain of Language’. In grounding trust for someone in a given situation or overall, we can explore our assessments of their sincerity, competence, reliability and involvement. By grounding trust, we can more knowingly engage in relationships, which should serve us well and enrich our life with less risk.

Between the two ends of the spectrum lie varying degrees of ‘prudence’. By being prudent, we can minimise risk by using guarantees to increase the probability of achieving our desired outcomes. For instance, I could double-check information; regularly check the progress towards achieving the task or go so far as to establish legal contracts. Being prudent is not only a way of protecting our interests, it can provide a means of building our trust in others by providing them a space to shift our assessments over time.

It is useful to appreciate the impact of prudence on performance and efficiency. The more effort put managing guarantees, the less time there is to do other things. This puts trust at the heart of organisational efficiency where less trust means less efficiency. There is a clear connection between higher trust and greater productivity that often gets lost in talk of soft skills.

Distinguishing trust as four separate assessments provides practical opportunities to enhance our relationships and more effectively deal with our breakdowns. The process of grounding our assessments of trust can pinpoint breakdowns in a relationship that we can address through conversations. For instance, say I have a poor and grounded assessment of your reliability when it comes to certain work activities. Understanding this, I can make requests designed to gain promises about how you will act in the future in those domains.