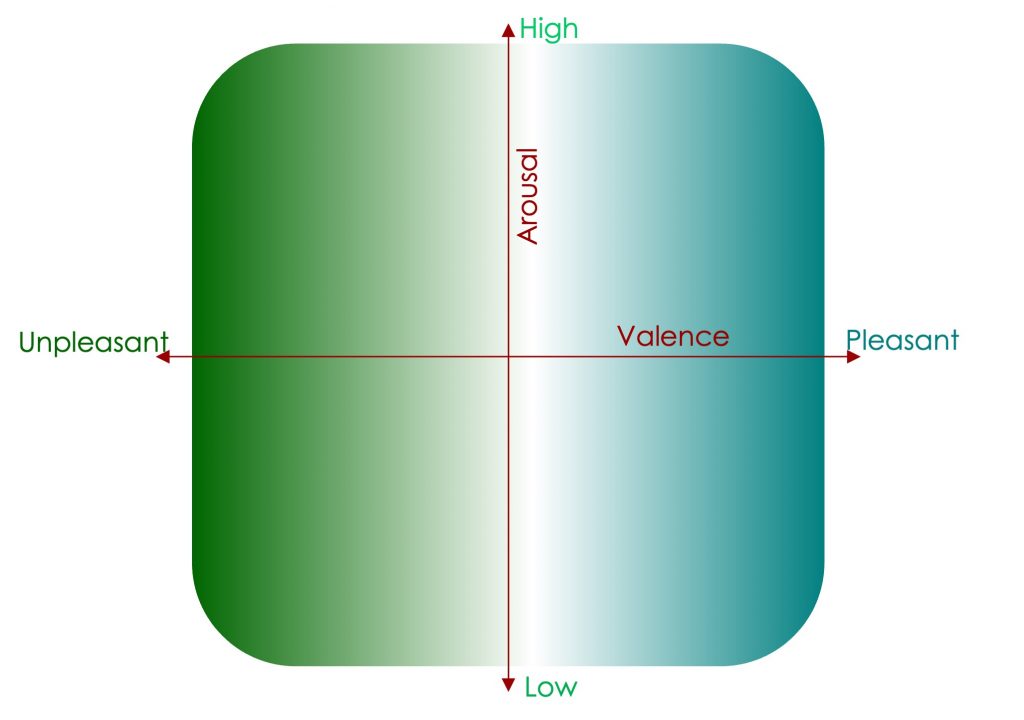

Interoception produces a bi-product known as ‘affect’, which is the sense of feeling that we experience throughout each day. Feelings that we have to make meaningful. Affect falls into two very broad categories – ‘Valence’ and ‘Arousal’.

Valence relates to how pleasant or unpleasant we feel whilst arousal relates to how energised we feel – low to high (calm to agitated).

Although interoceptive feedback about the state of our body’s resources produces affect, it doesn’t force us to act in any specific way, rather affect helps us create meaning. Our predictive brains constantly use past experience, including our past interoceptive experience, to predict what beings, objects and events will impact our body’s resources creating simulations that in turn alter our affect. In other words, affect does not direct action but provides the context within which we create our predictions, which may lead to our experience and action.

As our predictions always involve some affect, it colours how we experience the world. As a result, we often overlay our feelings onto what we observe – what is termed ‘affective realism’. In doing so, we are predisposed to experience affect as a property of what we observe rather than as our own experience. In essence, affect leads us to believe that objects and people in the world are inherently negative or positive; bad or good. In doing so, we experience affect as a property of an object or event in the outside world, rather than as our own experience. “I feel bad, therefore you must have done something bad. You are a bad person.”

However, a bad feeling doesn’t always mean something is wrong. It just means you’re taxing your body budget. And you do not have to actually do something for this to occur. Simply imagining a situation will have you predisposed to deal with it. For instance, say you have been told that there have been snakes sighted in the area where you are going to walk. As you go down the path, you hear a rustling sound up ahead. Your predispositions will have you primed to see a snake and your body will be prepared to respond regardless of whether a snake appears or not. It may even take some time for you to recover after you leave the path and the possible snake behind.

We might think that in everyday life, the things we see and hear influence how we feel, but it’s mostly the other way around. What we feel alters our sight and hearing. Interoception in the moment is more influential to perception and how you act than what happens in the world. As affect is the basis of our emotional life, this implies that our emotions are a key influencer of our perceptions.

Because it is based in our predictions, affective realism has real world effects. There are many cases of police, primed to expect a gun, shooting innocent people because they took out their smart phone. The police involved believed they saw a gun, even though one was not there, and fired. It is valid to say rather than the idea that seeing is believing, affective realism demonstrates believing is seeing. We are prone to observe what we expect to observe and often will be convinced we saw something we did not. It is important to appreciate these situations are not anomalies but common everyday occurrences.

Affect can be seen as an internal feedback loop informing us about the current impact on our body budget thereby allowing us to better understand our predispositions.

Affect gives us the basis for our emotional states, but something is required before we get to what are commonly known as emotions. We do not just feel good and bad, we feel joy, sadness and anger. So, what bridges the gap between affect and emotions? For an answer to that question, we must appreciate the way in which we create meaning about our experiences.