One of the most popular theories about the human brain is known as the ‘triune brain theory’. Attributed to Paul MacLean and popularised by writers such as Carl Sagan and Daniel Goleman, the triune brain model purports that evolution has developed the vertebrate animal’s brain in three distinct stages, but that only human beings have so far significantly developed the third stage responsible for language and rational thought.

The first stage of development was said to be the ‘reptilian brain’, found in all vertebrate animals. This is the small brain stem found at the top of the spinal cord and was said to be responsible for the regulation of our basic life processes such as body temperature control, blood flow, breathing and so on. The second stage of development was defined as the ‘limbic system’, which MacLean saw as the emotional centre of the brain. The third and final stage of development was said to be the ‘neo-cortex’ – the site of reasoning, language and logic. For many people, triune brain theory supported the idea of the ‘rational human’ and how we distinguished our emotions.

It has long been thought each emotion has a distinct brain circuitry thereby defining a neurological fingerprint that shows up every time we experienced a specific type of emotion. This circuitry stimulated certain physical patterns that we identified as anger, sadness and so on. This essentialist view of our emotions means that they must be generally consistent throughout all of humankind and speaks to the idea of an emotion as an entity.

The introduction of the MRI and the rapid expansion of neuroscientific research has undermined the ‘triune brain theory’ and, in particular, its application to our emotions. As neuroscientist Barbara L. Finlay, editor of the journal ‘Behavior and Brain Sciences’, says “Mapping emotion onto just the middle part of the brain, and reason and logic onto the cortex, is just plain silly. All brain divisions are present in all vertebrates.” Furthermore, this research has failed to find any consistent emotional fingerprints although proponents of the classical view of emotions point to hints at their existence. However, there is extensive research pointing to a lack of emotional fingerprints.

Researchers into human emotions have also ventured far and wide to examine how emotions compare in different societies. This research shows mixed results as various communities have differing views of emotional life.

Research into the human brain and its role in our being is leading to new interpretations of human emotion. A trailblazer in this domain is Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett, a University Distinguished Professor of Psychology at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. Based on her research, she has developed the ‘Theory of Constructed Emotion’, a theory painting a different picture of emotions that, in my view, better fits current neurological thinking. I invite you to read her work if you wish to further explore some of the arguments regarding the issues with the classical view of emotions.

Although her work challenges the old paradigm, it provides new insights into our emotional life and forms the basis for the concepts of moods and emotions in this approach. It all begins with the interoceptive network and the accompanying process of interoception. The interoceptive network in the brain is responsible for the management of the body’s resources together with registering the sensations created by this internal activity. Research shows this network incorporates all brain areas associated with our emotions.

Interoception is a process whereby the brain represents the sensations created by our internal motion and the impact on our internal organs and tissues, the hormones in our blood, our immune system and so on. It continually provides feedback to our predictive brain affecting our thoughts and actions.

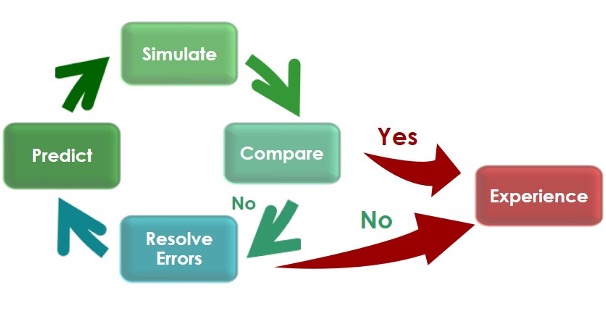

In making predictions, our brain not only makes meaning about our experience, it prepares us for the action required to deal with those predictions – our predispositions for action. This includes the internal movement of our body’s resources. For example, if the prediction relates to standing up, then this will require changes in blood flow to our legs, requiring changes in heart rate; our muscles will need resources for the dynamic changes required and so on.

We notice these changes in our body budgets (known as ‘allostasis’ as internal sensations through ‘interoception’. When you feel hungry, agitated, happy, nervous or in pain, this is interoception at work. These sensations are common to everyone and we notice them in two ways; how pleasant or unpleasant we feel (valence) and how calm or agitated we feel (arousal). Together, valence and arousal are known as ‘affect’ and this is the basis of our emotional life.