Human beings are emotional beings. It would be hard to imagine life without happiness, sadness, anger and the other emotions that are part of the rich tapestry of the human experience.

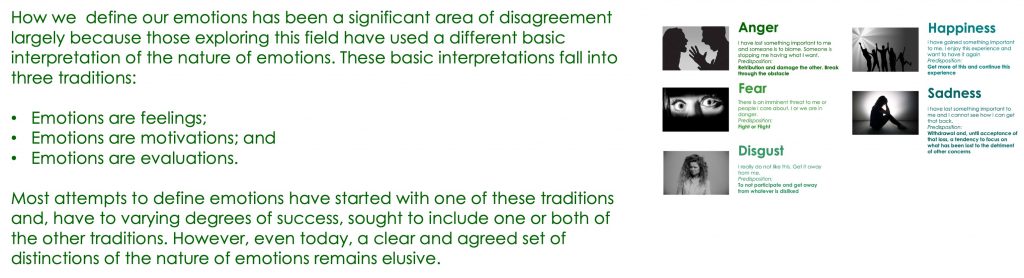

Yet defining our emotions has been a significant area of disagreement largely because those exploring this field have used a different basic interpretation of the nature of emotions. These basic interpretations fall into three traditions: emotions are feelings, emotions are motivations, and emotions are evaluations.

When asked most people in the western world will tell you emotions are feelings or sensations. We feel angry, sad or happy. Emotions are felt in the body. We can feel our own emotions and see other’s emotions. When someone’s face tightens and jaw clenches and you can see the tension and their readiness to attack you, you would probably say they are angry. And we know what angers means. We feel the sensations of anger as seen in sayings such as “my blood boiled” and “I was filled with rage”. These sensations form the basis of a social reality we share with others creating shared meaning about life.

Emotions as motivations speak to the resultant actions. We are motivated to hit something when are angry; to smile and laugh when happy and so on. In this interpretation, our emotions precede the initiation of action and predispose us to certain actions. They compel us forward into a future somewhat defined by our emotions.

Finally, emotions are physical experiences of our assessments of what is happening. They colour our world telling us what is good or bad. As we will see in the section ‘Affect and Affective Realism’, how we feel about someone or something is generally transferred onto them or it. If I experience good feelings when I am with you, then you are a good person. We assume our emotions tell about the nature of world.

Most attempts to define emotions have started with one of these traditions and, have to varying degrees of success, sought to include one or both of the other traditions. However, even today, a clear and agreed set of distinctions of the nature of emotions remains elusive.

For well over two thousand years, people in western cultures have tended to play down the role of emotions in human life preferring instead to elevate rationality. In ancient Greece, Plato saw reason as superior to passion and used the well-known ‘Chariot Allegory’ to reflect to how reason ruled the passions. Plato used this allegory to explain his view of the human soul. He saw reason as the charioteer pulling the reins to manage two winged horses and guiding the soul to truth. One horse represented our moral impulse and the other our irrational passions. To Plato, reason was the master of impulse and passion.

French philosopher Rene Descartes developed ‘Cartesian Dualism’ and the mind-body divide. The impact of Descartes’ philosophy on western thought over the past three hundred and more years is hard to understate. It dramatically promoted the idea of human rationality’s primacy over our physical and emotional being and further embedded the idea of ourselves as ‘rational beings’ throughout western societies.

As ‘rational beings’, the focus has been on the linguistic aspect of human beingness. There is also a separation of mind and body where the mind is seen as our rational self. As a result, we have sought to play down our emotions as much as possible, believing them to be an impediment to reason.

The belief that our rational self can control our emotional self has been enshrined in our justice systems, economic theory and many other domains, and is still the dominant paradigm throughout the world today.

Over the past few decades, the role of emotions in daily life has been revisited and a new appreciation for their impact has surfaced. The rise of ideas such as emotional intelligence and the pivotal role of emotions in domains such as leadership, relationships, behavioural economics and decision-making have led an explosion of books on the subject.

This interest in our emotions has also been fuelled by the accelerating pace of research and discovery in the domain of neuroscience. This work is starting to shed new light on our emotional life leading to new theories of human emotions and challenging the paradigm of the rational being. It is also starting to coherently bring together the traditions of emotions as feelings, motivations and evaluations.

Before going any further, there is an important question to address. Is an emotion a thing? This might sound like a ridiculous question to ask; but bear with me.

In everyday conversation, we talk about emotions as an entity; as something that exists within us that causes us to feel and act in certain ways. For example, I might say that I hit him because I was angry, I cried because I was sad, or I laughed because I was happy. Without thinking about it, we assume an emotion to be a definable thing that causes action. This idea is found everywhere. It is even put forward as a legitimate legal response when an accused invokes the ‘crime of passion’ defence; my emotions took me over and made me do it.

It is also easy to fall into the trap of believing that, if our emotions happen to us, we cannot easily shift them and we become a slave to our emotions. Anger takes me over and I cannot do anything about. Depression happens to me and I cannot do anything about it. All too many people fall into this trap and find themselves at the mercy of their emotions.

The idea that each emotion is a definable thing has been the basis for research into our emotional life for many years. But what if an emotion is not a thing, but an interpretation of our experience? An interpretation we learn from others. To appreciate why this might be the case, we need to return to our physiology and our predictive brain.